Gebhard Sengmüller

Slide Movie - Diafilmprojektor

New media art has its own heroes. The Austrian artist Gebhard Sengmüller is one of them. It also has its own traditions: every four years, Gebhard Sengmüller comes up with a new and amazing installation, seamlessly blending art and technology.

His vinylvideo – a room where video tracks are played back from vinyl LPs, using a traditional record player – has been traveling from one exhibition to another since 1998. Despite the retro feel, you can’t say that the viewer is transported into the past, because previous generations never utilized vinyl as video storage media. In fact, you’re transported to some kind of an imaginary “now”: if the inventors of PhonoVision back in the 1920’s hadn’t been so focused on producing disks and put more effort in building modified gramophones, the whole history of video recording and distribution could have unfolded differently.

In 2002, together with five engineers and programmers, Gebhard built a monster that he named Very Slow Scan Television. This computer-controlled gizmo injects paint into rolls of bubble wrap, creating images technologically and visually close to those produced by SSTV. The installation looks absolutely fascinating, and the absurdity of its purpose is astounding. In fact, the existence of a crazy and yet effective picture transmission method like SSTV is quite impressive as well. Who would’ve ever remembered that it existed if it wasn’t for VSSTV?

Gebhard’s works have loads of reviews. If it weren’t for him and several of his works, media archeology wouldn’t be such a hot area of study, and the concept of remediation, crucial for the understanding of the New Media, would have remained purely theoretical.

2006 saw the birth of the latest fruit of the his passion for the technologies on the brink of extinction: Slide Movie - Diafilmprojektor.

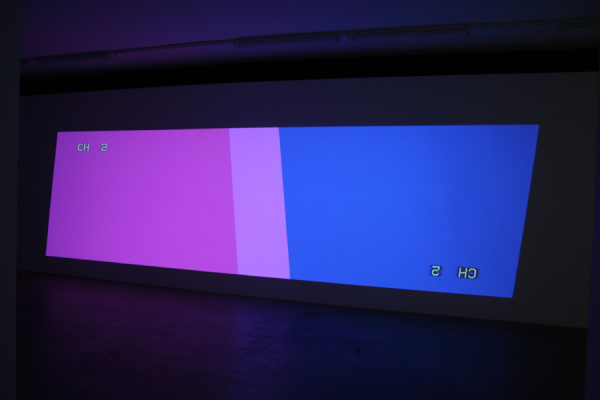

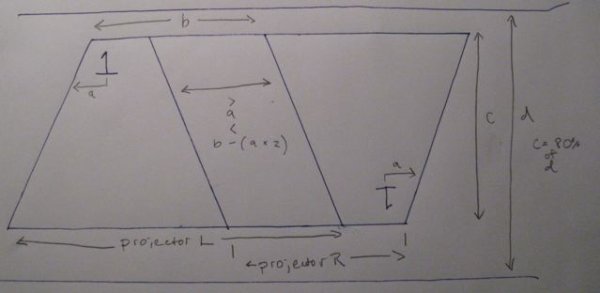

24 slide projectors, loaded with 1920 slides, are focused onto a single spot on the screen. A new slide is projected 24 times per second. This allows us to see 80 seconds of a movie, as if run on a very slow outdated film projector.

If you make a 180-degree turn, you’ll be able to see the apparatus itself – a mutant projector emitting twenty-four light bursts per second.

Or, you can close your eyes and listen to the sound, reminiscent of that of a film camera or a typing machine – which will soon become a fossil in its own right, - and reflect on a difference between analog and digital worlds.

Then, you can open your eyes again and turn your attention to the movie. The artist has chosen a rather typical moment – a shootout – in one of the most widespread genres, a crime film. At a first glance, it looks like a fairly generic scene, with the exception of one media-specific joke: one of the bullets hits the TV screen.

But in fact, this movie is far from generic. What we see is a scene from “Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia” (1974) by Sam Peckinpah, a movie that is still, many years after its making, a subject of the same controversy: does it belong to a top ten worst or top ten best films ever? It means, of course, that the movie is really good, and at the same time that it hasn’t been watched enough, that it’s misunderstood, underexplained or underanalyzed, that it appeared at the wrong place or at the wrong time. Like PhonoVision, that came ahead of its day, or SSTV, couldn’t attract more than a handful of fans.

We don’t normally watch movies on vinyl LPs or slide projectors – we have DVDs and video projectors for that. Neither do movie fans need the head of Alfredo Garcia when they have the perfected “Pulp Fiction” and “Planet Terror” at their disposal.

Then again, some of us don’t even need to see the installation or the movie - the title alone, Diafilmprojector, is enough to evoke strong emotions. But for that, you’d have to be a Soviet-born child of the 70’s, cherishing memories of a weird media experience: scary stories (pictures accompanied by text) appearing in a ray of light on the wall of a dark bedroom.